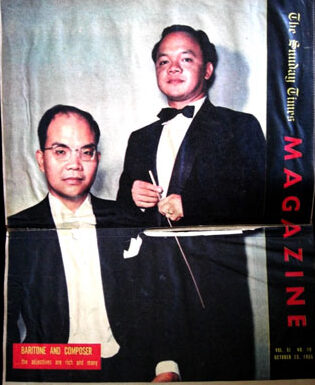

THE MOST OUTSTANDING YOUNG MEN IN MUSIC

The Composer Grabs All The Prizes

by Felix B. Bautista

Sunday Times Magazine, October 23, 1955

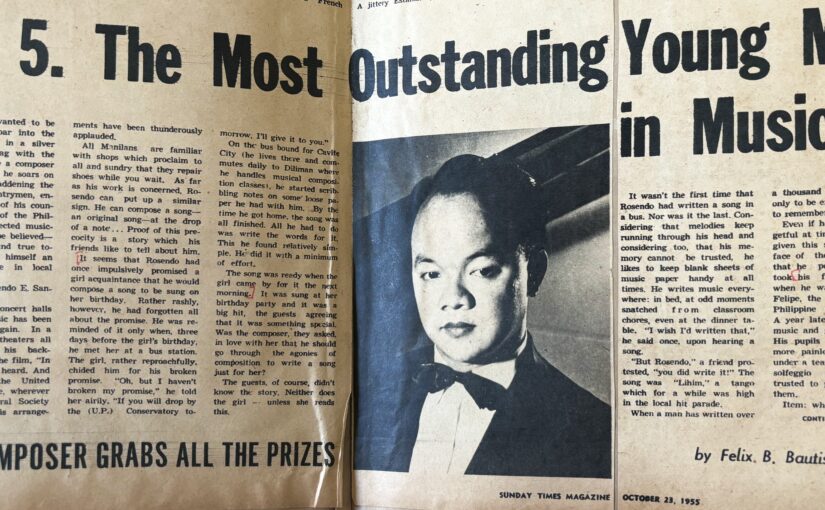

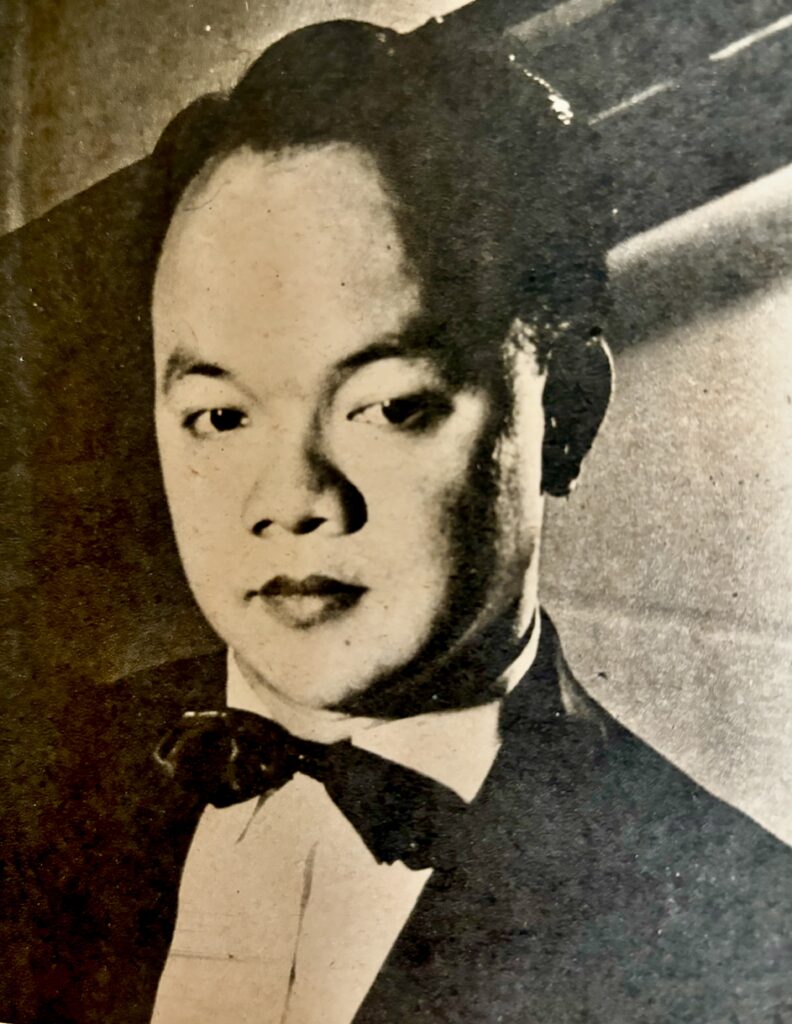

As a boy, he wanted to be a pilot, to soar into the wide blue yonder in a silver plane and play tag with the clouds. He became a composer instead, and today he soars on wings of song, gladdening the hearts of his countrymen, enriching the music of his country and—if some of the Philippines’ most respected musical savants are to be believed—heading straight and true towards carving for himself an imperishable name in local musical history.

His name is Rosendo E. Santos Jr.

In the leading concert halls of Manila, his music has been played time and again. In a thousand movie theaters all over the country, his background music for the film, “In Despair,” has been heard. And in the cities of the United States and Europe, wherever the Harvard Choral Society has performed, his arrangements have been thunderously applauded.

All Manilans are familiar with shops which proclaim to all and sundry that they repair shoes while you wait. As far as his work is concerned, Rosendo can put up a similar sign. He can compose a song—an original song—at the drop of a note…Proof of this precocity is a story which his friends like to tell about him.

It seems that Rosendo had once impulsively promised a girl acquaintance that he would compose a song to be sung on her birthday. Rather rashly, however, he had forgotten all about the promise. He was reminded of it only when, three days before the girl’s birthday, he met her at a bus station. The girl, rather reproachfully, chided hm for his broken promise. “Oh, but I haven’t broken my promise,” he told her airily. “If you will drop by the (U.P.) Conservatory tomorrow, I’ll give it to you.”

On the bus bound for Cavite City (he lives there and commutes daily to Diliman where he handles musical composition classes), he started scribbling notes on some loose paper he had with him. By the time he got home, the song was all finished. All he had to do was write the words for it. This he found relatively simple. He did it with a minimum of effort.

The song was ready when the girl came by for it the next morning. It was sung at her birthday party and it was a big hit, the guests agreeing that it was something special. Was the composer, they asked, in love with her that he should go through the agonies of composition to write a song just for her?

The guests, of course, didn’t know the story. Neither does the girl—unless she reads this.

It wasn’t the first time that Rosendo had written a song in a bus. Nor was it the last. Considering that melodies keep running through his head and considering too, that his memory cannot be trusted, he likes to keep blank sheets of music paper handy at all times. He writes music everywhere: in bed, at odd moments snatched from classroom chores, even at the dinner table. “I wish I’d written that,” he said once, upon hearing a song.

“But Rosendo,” a friend protested, “you did write it!” The song was “Lihim,” a tango which for a while was high in the local hit parade.

When a man has written over a though sand compositions, it is only to be expected that he fail to remember all of them.

Even if he is somewhat forgetful at times, he can be forgiven this shortcoming in the face of the manifold virtues that he possesses. Item: he took his first music lessons when he was 10 under Julian Felipe, the composer of the Philippine National Anthem. A year later, he was teaching music and getting paid for it. His pupils thought it was more painless to study music under a teacher who, when the solfeggio palled, could be trusted to play patintero with them.

Item: when he was a freshman in high school, at the ripe old age of 12, he was doing the musical arrangements for one of Cavite City’s two topnotch bands. And his arrangements, then as now, reflected his bold treatment in instrumentation.

Item: as a member of the defunct Municipal Symphony Orchestra and a a player of Maestro Federico Elizalde’s Little Symphony, he has been called “one of the best tympani players in the world.” Source of this tribute was a ranking delegate to the recent Southeast Asia Regional Music Conference held here. This delegate, by his own admission, had heard the tympani players of the best symphonies in the United States and Europe.

Rosendo inherited his music from his mother, the former Castora Salazar who, as a young girl in pre-Revolutionary days, was an accomplished harpist. Today, she is in her seventies and doesn’t play anymore. But she still loves music and encourages Rosendo in his work. His father’s inclinations are somewhat more mundane. He lives and breathes politics and was, for two terms, mayor of Cavite. He is a vigorous 70 today, and his interest in politics hasn’t dimmed one whit. His biggest disappointment, perhaps, took place when, against his wishes, his son took up music instead of law.

Ever the devoted son, Rosendo still lives with his aged parents in Cavite City. As a U.P. faculty member, he could very well take up residence in Diliman, but too many things demand his attention in his home grounds. He is the conductor of the Sangley Point Choir which is made up of a group of American servicemen, their wives and their dependents. He also heads the Philippine Navy Choir which regularly assists at Catholic services on Sundays and holidays. In addition, he still does the arrangements for the two Cavite City bands.

These chores, topped by his 13-hour weekly teaching load at U.P. Conservatory, probably explain why Rosendo has not married. There is too much music in him to leave room for wedding chimes.

His dream of going abroad may materialize sooner than he thinks. At present, the screening committee on the UNESCO Fellowship for Creative Composer is giving serious consideration to his application He and another composer have the inside track and, as of this writing, it is still a toss-up as to who will get the coveted scholarship.

If the committee gives the nod to him it will be in recognition of his distinct contributions to Philippine music. Also, to a more or less equal extent, in tribute to his truly excellent record in various competitions held for composers during the past nine years.

Rosendo first became the object of attention when, in 1946, he won the U.P. scholarship contest. This enabled him to go through the regular four-year music course at no expense to him. To prove that his initial triumph was no fluke, he won again the following year the U.P. Alumni Hymn Contest. Although just a student, he won over veteran composers and professional music-makers.

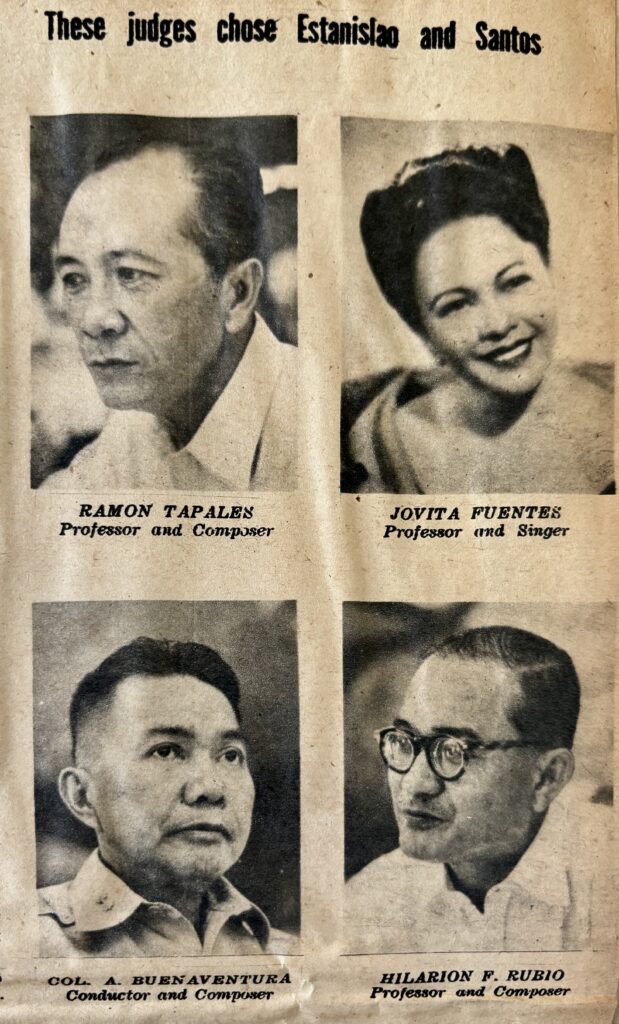

Winning competitions has since become routine. In 1950, his march was adjudged the best in the contest sponsored by the University of the East. His composition is now the official U.E. March. To commemorate the fifth anniversary of the Philippine Republic, another contest, this time for an official Philippine Republic March, was held. The board of judges made up of such musical titans as Herbert Zipper, Col. Antonio Buenaventura, Julio Esteban Anguita and Bernardino Custodio, gave the nod to Rosin’s entry. This was in 1951.

In 1952, he added another feather to his cap. This time it was the Hymn Contest sponsored by the Boy Scouts of the Philippines. For the BSP March, he got honorable mention. This was a departure from his monotonous habit of garnering first prizes. His only consolation was that no other entry was given first prize, all the winners merely getting honorable mention.

By the time he won the Harvard Song Contest (for his arrangement of the popular folk-song “Sampaguita”), Rosendo’s cap had so many feathers it was beginning to look like an Indian chief’s headdress. If that song today is hummed by people living in places where the Harvard singers have performed, we can thank Rosendo.

Right now, he is putting the finishing touches to his operetta, “Hiyas ng Nayon” (Jewels of the Barrio). The story of three girls named Ruby, Esmeralda and Perla, it is a one-man effort. He wrote the story-line, furnished the dialogue, composed the music. It will be performed late this month by the U.P. Conservatory under the auspices of the U.P. Student Council.

One other composition of his is due for an early unveiling. This is the Mass he was specially commissioned to do by Fr. John P. Delaney, S.J., chaplain of the U.P. It will be sung when the new chapel is inaugurated.

His “Piano Concerto in G Minor” has been performed repeatedly, as has his dissonant “Mountain City Suite” which he composed during a vacation in Baguio.

This soft-spoken, wavy-haired, fair-skinned 33-year-old stands five-feet-three inches and weighs a slightly hefty (for his size) 145 lbs. His lack of height, however, seems to be his only lack. He has promise, he has zeal, he has consistency. In Philippine musical composition, he’s a big man.